At this time of year crystal balls come out and pundits have a go trying to predict trends for the coming year. Central to macroeconomic forecasts, and in turn the potential for stock returns, is what GDP growth may do.

In China’s case predicting the trend of GDP growth in 2022 is easy. It will, most surely, be lower than whatever it turns out to have been in 2021; and, a deceleration of GDP will be bad for stocks, right?

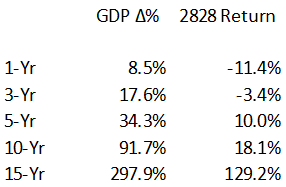

Lets first start with a look at what an investor in the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index tracking ETF, #2828 (a proxy for China stocks in general throughout), has been returned in the last 1,3, 5, 10 and 15-years together with a look at what China’s GDP has done over those same periods.

[Total return data for the ETF has been obtained from Webb-Site 2828 total returns to the last close and GDP data from the IMF China GDP 2007~2020, their guess for 2021. Return periods are calendar years.]

What’s obvious is whatever rate of GDP you’ve been delivered in the past you’ve received a lower rate of return on your stocks.

Right away then we can dispense with any notion that strong GDP growth in China produces investment returns that directly reflect this.

This is a phenomenon observed in other emerging markets and has to do with demand for capital in rapidly growing economies (enormous) which leads to serial dilution via (humongous in China’s case) stock issuance.

Mr. Thomas Picketty in his 2013 book Capital in the Twenty-First Century noted that long term returns to capital were higher, in his studies, than economic growth. China stock investors’ recent experience has been, in fact, completely the opposite!

Ah but… Surely the ‘pace’ of economic growth or it’s rate of change should indicate potential for investment return even if the absolute level doesn’t?

Here we have more luck. In our sample period we have 14 observations from 2008~2021 and in nine of the fourteen years when the rate of economic growth rose or fell stock returns went in the same direction.

However, when they diverged the divergences were stark. In 2009, when GDP growth decelerated modestly from 2008 (9.7% => 9.4%) our stock-proxy returned 63%. Growth again decelerated in 2012 (2011 9.6% => 7.9%) while our ETF returned 17%. In 2019 growth again slowed and the ETF gained (6.8% => 6%, +13.4% respectively). Finally, in 2021 so far, the economy has accelerated from the knocked-out 2020 (2.3%) to an 8.5% clip whilst our 2828-ETF has returned -11%.

Betting therefore on stock returns following the rate of change of GDP growth has been a winning strategy until, and in big ways, it hasn’t.

In Conclusion

China’s status as a developing economy has robbed investors in recent years of reliable returns associated with it’s top-line economic progress (the stock over-issuance problem, mainly). The level and rate of change of it’s economic growth has therefore been an irrelevance in terms of predicting bottom-up stock returns and 2022, most likely, will be no exception.

To this note’s title then. Analysis of recent trends in China’s economic growth and stock returns reveals little of reliable value and analysis that attempts to link the two lacks a basis in recent observation.

China’s GDP growth will surely fall sharply in 2022. It’s companies’ stock prices though may do very well. Or not. Good luck!

Nial Gooding

Saturday, November 20th 2021